⁂ The Impossibility of Beauty in the Mind of the Undocumented Artist; Pt 1 Julio Salgado and Perduring Ephemera

Infantilization, Capture & Deskilling in Migrant Art for the Board Room. An analysis of Julio Salgado, Yosimar Reyes and Undocumented Cultural Production.

for FrijoLiz. for Myisha Arrellano.

Thank you Alan Peláez Lopez for your thoughts and your support when I proposed writing such an essay.

“…But what is the work of the Work?:” — Miwon Kwon, paraphrasing a colleague.

The undocumented immigrant movement in the United States is conspicuous for its failure to produce global artists or writers whose work is lauded for its artistic merit and not for their historical adjacency to movements which they covered in their ephemera. With the exception, possibly, of Karla Cornejo Villavicencio in literature and Dillon Sung in the visual arts (there are more), undocumented artists with political perspectives who have illegally entered into mainstream or academic consciousness have foregone any concern for the formal qualities of their work and are hostile towards quality and aesthetic concerns. The term artivism or art activism is deployed in their biographies and the introductions to their paid talks or panels in air conditioned foundation multi-use spaces while undocumented activists, illegalized migrants who risk deportation, disability and death, bear the heat of the sun and the glares of police. Most insultingly, they are unconcerned with the work of their œuvre, the ideological and political impact of the ephemera and images which they birth into the world and which are a form of cultural and symbolic violence against immigrants. Their green cards came at the price of intellectual dishonesty and we are now tasked with producing new work and producing new cultural workers to correct a distorted record and a defaced archive.

Undocumented artists, I argue, must be näifs or perpetual autodidact craft makers, they must produce work which betrays no experience and minimal theoretical concerns. They must be docile and insipid, suitable for covering books produced by universities with handfuls of undocumented students and for the offices of professors in ethnic studies who do not engage with the critical and theoretical work of undocumented theorists and philosophers directly. The work itself must amount to a slogan which is probably also written in the image, impossible to analyze or to study for its artistic and aesthetic merits because of its vapidity and the intellectual cul-de-sacs they trap the consumer into. We can see this in the work of Julio Salgado and Yosimar Reyes—respectively, an undeniably talented artist whose work and skill I saw in person in San Ysidro, California as he carved and taught others to make woodblock prints entirely unlike his most circulated images and a poet from the Bay who seems allergic to poetics and whose work produces scansion that amounts to and leaves the reader with flatline.

The fungibility for less than 30 pieces of silver of undocumented identity is the concern of the work, thought not knowingly. The establishment and maintenance of an infantilized, always-innocent, and infuriatingly earnest cultural imaginary which gives undocumented youth seeking any identity only a spoiled one is the legacy of this work.

Julio Salgado— Perduring producer of perduring ephemera.

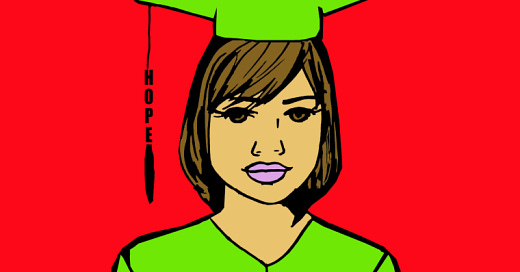

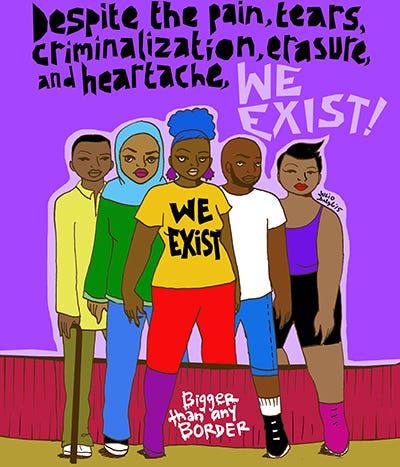

Beyond the fact Julio Salgado is undocumented and identifies as queer (he may be formerly undocumented now, probably still queer), the biographical details of the artists life are irrelevant to understand the work. Salgado makes digital images which festoon books, the above are color samples and excerpts taken from the cover image1 of We Are Not Dreamers: Undocumented Scholars Theorize Undocumented Life in the United States (Duke University Press, 2020, image from 2015) by Dr. Leisy Abrego and Dr. Genevieve Negrón-Gonzales, which I received in Guadalajara signed by Dr. Abreigo herself. The work includes an essay on the experience of UCLA students which I contributed to as a survey respondent.

The artwork features five figures standing with one foot behind what appears to be a wall, which we know is a border wall likely at the US-Mexico border as suggested by “Bigger than any Border,” written to simulate dripping spray can paint. The five figures stand defiantly, we are to believe because of glances we can just about perceive return our gaze in the Mulveyan fashion (not the Lacanian). The background is stark, garish fuchsia which is out of accord with the other saturated hues which are applied in flat fill layers outlined by jagged lines in an MS-PAINT style of the 90s internet. Without concern for the folding of fabric on the body, on the central figure’s goldenrod colored t-shirt with bell sleeves, Salgado states the obvious, “IBIDEM!,” undisplaced or manipulated, a statement which we are not allowed to question as the artists’s bravely states “WE EXIST,” over the figures in lilac. The hands are, I’m assuming, foreshortened as not all figures have all four fingers and thumbs—perhaps a nod to Salgado’s disability activism which reaches its apogée in the figure holding a cane—as are the feet which connect to the calves of the figures without concern for anatomical drawing or the existence of joints. This is uncertain as the frontal perspective and the lack of detail in the hands leaves us only to wonder if the hands are foreshortened or if they have been mangled.

Like much of the rest of Salgado’s œuvre, the use of tones and shades is absent, we are meant to imagine the folds in the clothing or on the human body, which he might occasionally gesture at with lines—usually around the breast of women or his own in his shirtless self-portraits. The use of minimal shading and uneven lines creates unintended moments of mirth in Salgado’s otherwise joyless depiction of disabled, allegedly undocumented subjects. We do not know but can assume they defiantly stare at us as they declare in unison, “IBIDEM.”

“Ojos tapatíos: uno que baila y el otro que zapatea”

Salgado’s art and its aversion to full mimetic representation, color accord, anatomical drawing, composition, and the other formal qualities of art could be understood and we can be so generous as to understand this as a nod to his printmaking drawn from his uncirculated woodblock prints, silkscreens and other physical media (stickers?). However, the repetition of this question in his work is astonishing as it has not changed significantly over years. It betrays a lack of aesthetic or theoretical ambition even as Salgado’s career ambitions are themselves quite notorious and have now illegally entered into the audiovisual media.

The resulting work is utterly childish, utterly infantile. It is a work which exists to bear a slogan, “IBIDEM.”

How can we explain that this is the most circulated undocumented artist producing work about immigrant rights or immigrant identity? To whom does this appeal to. Betraying my own bias, I see Salgado’s art only on the walls of people who are not undocumented, neglected in the offices of Al Otro Lado’s Tijuana bunker, collecting dust on the desks of Chatsworth immigration attorneys who charge fortunes for those in abject poverty who can barely scrape together five-hundred dollars to remain out of chains and out of coffins.

It appeals to them and to the publishers and the organizers of panels about undocumented activism and art absent either activism or art, because of their instantaneity, because of their rapid deployment of a stock phrase, “IBIDEM,” to instantly brand their events and their publications and drape them in the bromides of the undocumented immigrant movement already past their half-life.

This infantilization is ironic given Salgado’s own apparent rejection of and bristling at the infantilization experienced by undocumented migrants in another self-portrait (this time wearing a shirt, the same goldenrod blouse without the iconic letters, “IBIDEM!”) bravely defying ageism in the undocumented movement. (2021)

This irony elicits immediate scorn. How are we to protest our infantilization and our perpetual childhood when Salgado produces art intentionally conceived to elicit thoughts of childhood art, näive art and student juvenilia? I argue, and I believe, that our temerity and our docility which prevents us from producing work which might betray formal training or the acquisition of skills trough autodidact learning is a tell, it’s a sign of our own inability or indecision over whether we are capable of being adults or capable of aspiring to more than calques and t-shirts sold at Old Navy.

The infantilization of undocumented adults in art produced by undocumented artist for the consumption of non-undocumented scholars, foundation luncheon gatherers and others is the visual encapsulation of the undocumented movements political capture.