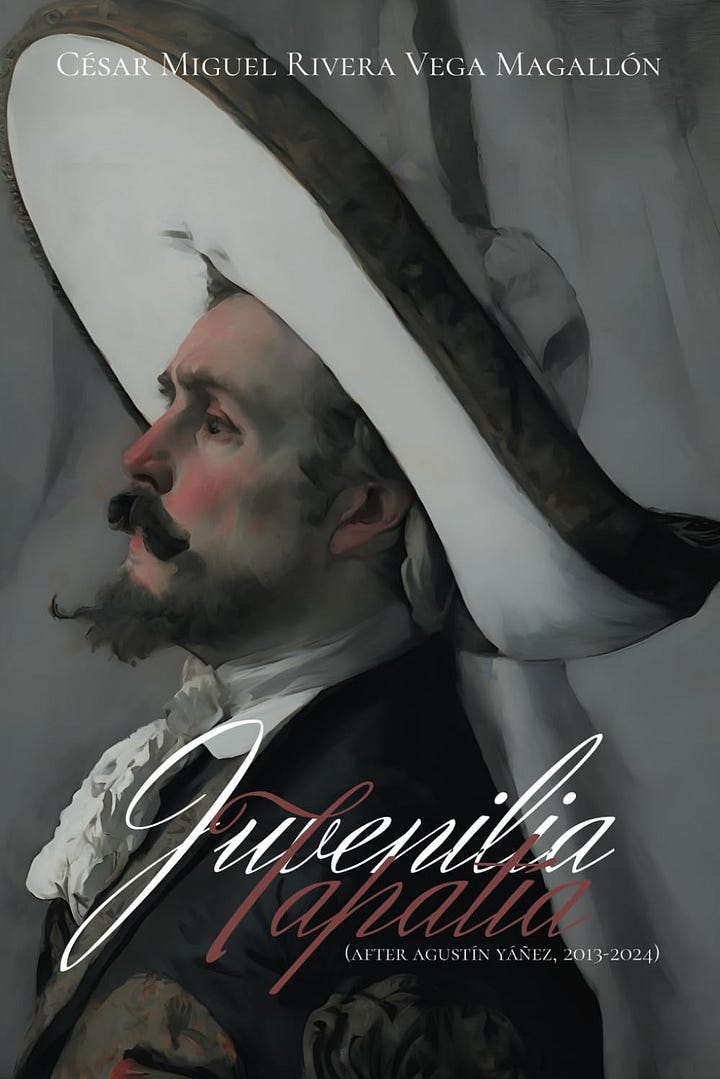

Gaslighting the Ragpicker (Juvenilia Tapatía, bonus essay)

A formal analysis of Manet's Ragpicker (100/100%)

In celebration of Best New Selling Mexico History (!) Debut, here is another piece of Juvenilia. I believe I was the first to write about the use of gas lighting in Manet’s Ragpicker at the time, the literature review of prominent Manet scholars didn’t reveal a single mention in this or other paintings in 2013 when I made the Dean’s List at UCLA (All-A’s) my first quarter, though others certainly have since.

César M. Vega Magallón

Hector Reyes

Art History 110F

November 8, 2013

Standing at over six-feet tall, The Ragpicker is an imposing piece that dominates the wing of the Norton Simon where it is housed. It looms over the viewers whose necks crane to meet the obfuscated, red gaze of the figure, a tired, older man whose clothing is torn, dirty and worn. The garbage that lies in the corner of the tableau floats in space; the ragpicker is thrust outwards towards us. The flatness of the depiction is disconcerting, an effect of the imprecision of the paint and a background that refuses to recede or reveal a vantage point. In concert, Manet’s formal decisions create tension in the work that is beguiling and intriguing.

When first approaching the painting, one is struck by the qualities of the brushwork. In comparison to the still lifes that hang beside The Ragpicker, the brushwork is looser and more evident. Near the bottom of the figure’s tunic large, dark brown and black strokes allude to folds and creases in the fabric. There is no attempt to disguise the wide, angular sweeps of the brush by blending or by the application of carefully layered translucent applications of paint. Elsewhere, such as the right arm of the figure, Manet employs rounder brushes and thicker lines to give the sleeves a sense of mass and volume. Dark strokes move vertically and diagonally down the arm of the figure, intersecting with and superimposed on lighter yellow and grey daubs which are also applied without an attempt at blending into a cohesive, smooth surface. The application of the thick lines over the smeared areas of grey and creams, likely the result of painting alla prima, emphasize the materiality of the paint. Because of this treatment, the dirty, unkempt appearance of the tunic is all the grimier and all the more pitiful.

On the figure’s bag, especially the closed mouth, the brush strokes are shorter and sharper. Manet has used dark-brown paint over four tones of yellows and green-tinted browns in short, slightly-angled horizontal sweeps that create the raw, unhemmed edges of the ragpicker’s bag. To construct the face of the figure, the paint is applied in a less gestural fashion. The hard edges are gone and the soft greys that suggest a beard blend slightly into the face of the figure. Manet then resorts to daubs of warm red-orange and light yellows to create the ruddy complexion of the man, the brightest of which hint at the reflection of light from skin. The eyes are only slightly distinguished from the rest of the face by thin brown daubs that create the creases of the bottom lids and slight black circles that emulate pupils.

The broken bottle at the foot of the man surrounded by vegetal waste is depicted in the manner of a sketch. Manet relies mostly on color, the yellows that may depict fruit rind, greens that may be leaves and a red that may be fruit or the dried remains of roses or carnations, to separate the objects from one another. The objects are difficult to identify even when the ochre background does not devour the detail towards the bottom left of the painting. The broken bottle whose silver foil wrapping is depicted with strong flat, diagonal streaks of multiple grey tones that flower into the mottled foil that once covered the lip recalls the broken glasses and empty vessels of memento mori. The effect is only to give impressions, of a cotton tunic, burlap sack, skin, eyes, beard, glass and vegetation, instead of faithfully and meticulously translating the reflective and textural quality of the materials. The instantaneity and energy of the painting belie the static posture of the figure and give the overall composition a sense of vivacity that is otherwise absent.

The ways in which Manet has painted The Ragpicker is a significant factor because they it has implications for other formal elements of the painting, most evidently line. All around the body a conspicuous black outline separates the figure from the background and establishes its mass, not unlike the edges of a woodcut or etching. Around the right hand that clutches the bag the lines become thicker and darker, aggressively calling our attention to the visual flattening of the arm tight against the body. The strength of the outlining defines this as the focal point of the painting. From there, the strong black lines of the tunic guide the eye through the painting, from the hand, down through the bag, to a tear, around the hem of the tunic, to the walking stick and wan blue pants, and finally down to the grey shoes which lead the eye towards the garbage strewn about his feet.

At this point, line vanishes from the painting. We are left with soft swaths of ochre and brown that do not coalesce into the ground the figure presumably stands on. The effect is reminiscent of photography, but may more likely refer to a gas lamp beyond the frame of the painting. Below it, the tepid yellow light casts short shadows, saps color of its vibrancy and creates a diffuse circle of light that the ragpicker has stepped into. The light source contextualizes the image: it may be a street scene taken from the nights in a Paris that had been transformed by public lighting.

The ragpicker does not emerge gracefully from the darkness, as we would see in the work of Rembrandt or Velásquez, rather he is superimposed onto it. The effect is the primary source of compositional tension in the image. We cannot be sure of our vantage point without a recognizable background. The viewer can see both the top of the man’s hat and the foreshortened depiction of his shoes, including hints of their undersides; we seem to be staring both frontally onto the figure and looking down slightly from an elevated position. This lack of a clear, illusionistic perspective without the aid of gradation of shadow thrusts the man out towards us. Not even the refuse at his feet serves to separate him from the frontal plane of the image. However, the posture of the figure, with both his feet and walking stick firm on the ground, insist on a ground and space that should separate the figure from the refuse and from the viewer.

As fascinating as the internal tension within the space of the painting is, it creates a problem for Manet. The starkness, abstraction of objects and figure, and the instability of space within the painting repel the viewer’s gaze, even as the turned-away view of the ragpicker seems to invite us to linger. The painting is uncomfortable to look at in all its flatness; the viewer’s eye wanders down and back up the strongly delineated outlines only to be left with an empty background to ponder.

To combat this fatigue, Manet expends considerable energy on building volume within the painting. The rhythmic use of the many slightly curved lines that create the hem of the tunic and the folds above create the space that swallows the legs at its umbrous opening. Similar rhythm is seen in the downward shadows that create the draping of the torn pants. This is visually pleasing, but serves an alternative purpose. Together, the tunic that seems too large and the pants that are too long work to suggest subtly a gaunt anatomy underneath. This suggestion of volume is notably absent in the bag the figure carries. It lays flat against the chest and shoulder and then hangs vertically against the back of the ragpicker. Its emptiness is emphasized by the slight way in which the tones become brighter near the elbow. This fixes the temporal point in the narrative of the ragpicker’s walk; he has just begun and has not found the rags that he will need to sell. He may not find them. Through the construction and contrast of volumes, Manet has simultaneously reinforced the pathos of the narrative and strengthened the visual appeal of the image.

Through these formal techniques, the artist elicits the sympathetic response of the viewer. We are urged to acknowledge our feelings of pity about the terrible condition the ragpicker lives in. But, Manet has not painted the story of a particular ragpicker, but rather the image of the ubiquitous ragpicker on every street in the city. The viewer cannot crystalize the vague emotional response because the tableau rejects a sincere emotional interpretation. When we stare into the rough skin of the face or the hands, the mass dissolves into the daubs of paint. The earthy, monochromatic palette, the stationary posture, the lack of clarity in the depiction of objects all create obstacles to our emotional attachment to the subject matter. The tension between space and perspective that results in the frontal nature of the painting is disconcerting; our eye wanders around, attempting to make sense of a painting that for its size seems slight and insubstantial for the lack of illusionistic space or detail. The Ragpicker challenges the gaze and emphasizes our voyeurism; the viewer is constantly made aware of the act of looking, of the intellectual and physical exercise that is involved in the gaze. It is this challenge to the act of looking that is The Ragpicker’s most fascinating quality.