We were halfway through reading Macbeth when, on March 27th, 2006, a handful of students among ~2,500 walked out of our campus in Lancaster High School (LNHS) to join the nationwide blow-outs provoked by a House bill that we were told would criminalize paramedics performing CPR or priests performing transubstantiation. The news of the blowouts spread through our campus the week before that Monday. It ignited the racial powder keg on campus that had persistently and consistently ignited into race riots on campus that, only two years before, had forced police on the roof to watch students run home after a mass-shooting threat had been made against “all Mexicans wearing white shirts” (we had uniforms then, a white or blue polo with black or blue pants). Suspension or expulsion threats were made by the principal and vice-principals and we were sternly warned in every class that truancy was a crime, one which could lead to deportation or the arrest of our parents.

I don’t recall the name of my male classmate who reproached those of us who stayed firmly in our seats in English class as he walked out of campus to join the protests across the region, but I cannot forget his anger. Eyes quivering with adrenaline and dispensing disappointment, jaw perpendicular to the scuffed carpet, he looked at each and every one of us before he alone left the classroom and vanished into the cavernous atrium of our campus. I slumped into my desk. For the first time I felt as if I was presented with a political decision and in the moment I felt as if I opted for caution and prudence, though now I wonder if my participation would have forced me out of a second closet a full six years before I would do it in front of Jose Antonio Vargas and Rudolfo Acuña at an event at CSUN. Prudently and cautiously, I remained silent, even during lunch as black students jointly protested in the quad while the girls with drawn-on eyebrows and pressed burgundy hair cursed at the security guards and the overwhelmed campus Sheriff’s deputy attempting to reign in another sudden eruption of anger that left the Mormons once again trapped in a froth of expletives and raised fists. A bottle of urine flew through the quad and hit a football player in the face; one of many piss projectiles launched over four years. I withdrew to the two-storied safety of the yearbook room where I, as editor in chief, built a personal Porfiriato for myself printing falsified hall passes that allowed anyone who could afford my toll ($15) to leave campus for as many periods as they liked. The guilt I felt for remaining in the shadows and not joining the blowouts found its outlet in my schemes to fix Homecoming Court elections and “Pacesetters” for posterity and for eternity; a Porfiriato indeed, only I know the true results of many sham elections.

These bursts of sudden political consciousness and direct actions on our high school campus had by then become commonplace. It was a necessity to shuffle and dodge a coagulating crowd of angry teenagers since at least 2002, when Piute Middle School became beautiful and anarchic and rained milk cartons and baked lapidary upon the heads of administrators the days after the vote to authorize of the Iraq War. A generation of No Children Left Behind, pregnant teenagers and I, an inconsistent student in GATE classes enrolled in a school where only 7% of students left with proficiency in math, entered high school as politicized and battle-hardened activists. My freshman year of high school was marked by the re-election of George W. Bush and the muffled sobs of male classmates who repeatedly said, “I don’t want to die in Iraq.” Kerry and the failure of America’s patrician class to cool the bubbling tar of White anger set the stage for years of expulsions, suspensions, drop-outs and constant racially fragmented anger on our high school campus that truncated more than one young person’s future. I am too sentimental to sustain my argument that those truncated futures set the stage for our present political truncation, but I posit it here.

Even after the moment of anger had passed and I could count on both hands the number of students who walked out, I recall the other Mexican and Chicano students on campus discussing if they might still join them. The remainder of the day was a constant debate characterized by the unanimous and consistent answer of the adults, teachers and cafeteria workers alike—silence, broken by the exact same sigh.

A whistling sigh, a sigh with an upwards intonation. An exasperated sigh. A sigh in agreement? Only in Sheppy’s (Mr. Shepardson) AP U.S. Government class the next day did I find myself with the words fumbling from my mouth in protest of the seeming calamity unfolding before us. Mr. Shepardson never revealed his personal political leanings to us, though we plied at every angle to tease it out (I personally believed he was a Republican). He was the man who put Frederick Douglass before me and, I recall with stenographic accuracy the day he chuckled with endearment as I erupted into red-faced anger the year prior when my classmates debated the prudence or legality of the Mexican Cession. “It led directly to the Civil War,” chuckled Sheppy. “It expanded slavery, and Protestantism” I objected. But, the day after a blowout which fizzled out, Sheppy seemed as mirthless as any of us.

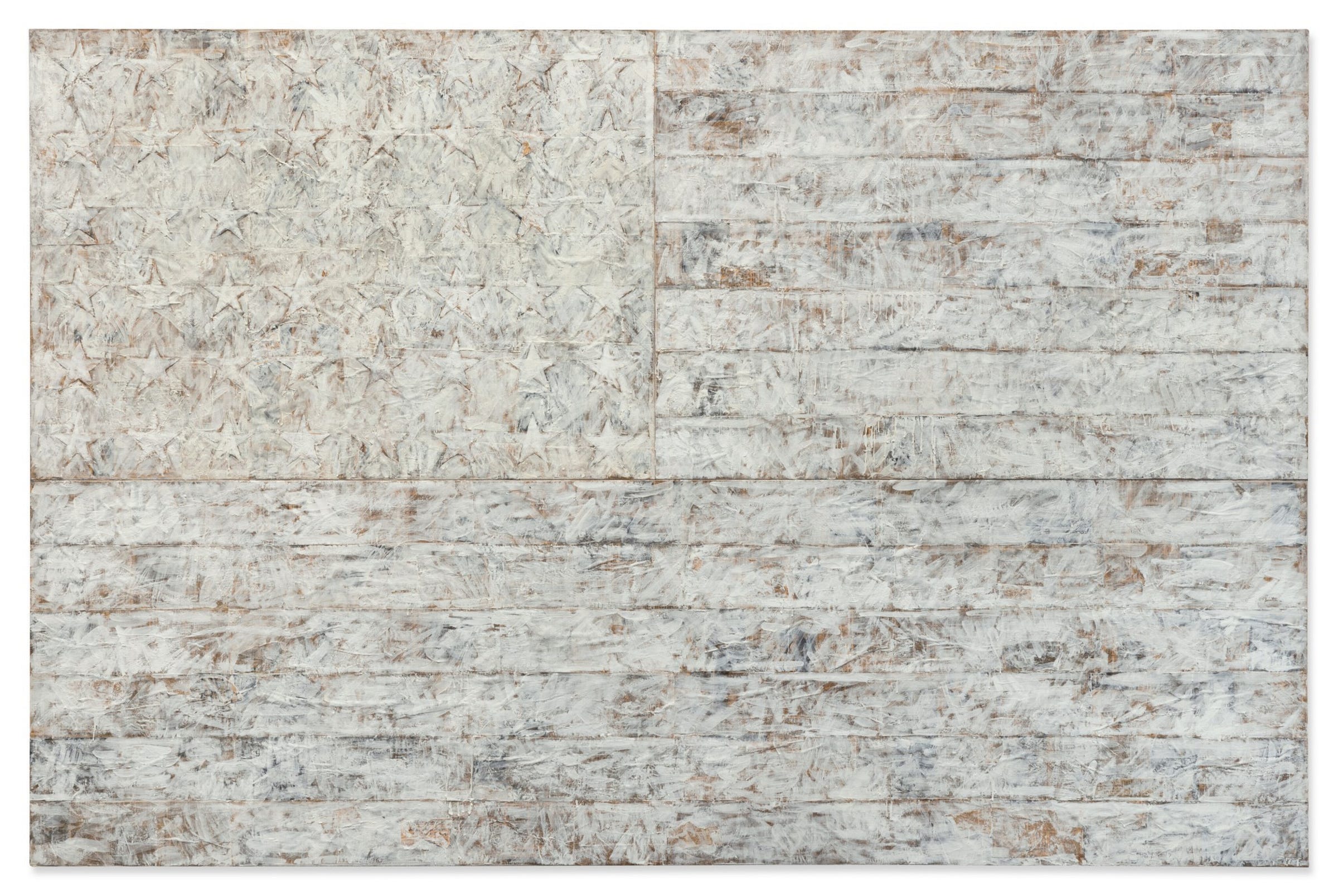

It seems astonishing to remember the ease with which he reanimated Marbury v. Madison before our astonished faces and then the patience months later with which he heard our teenage anger over the Supreme Court’s decisions in Dred Scott v. Sanford or the unanimous relief as we read the decision in United States v. Wong Kim Ark. My Cornell notes were punctuated with sighs which more than once broke out into stifled tears alone in my room the night before his class. I could not explain to Sheppy that I saw an expressionist portrait of myself in those decisions. I could never overcome my fear and show him the sepia-toned photograph of my childhood embedded deep in his lesson on Plyler v. Doe. In contrast to the Monday before that Tuesday, I remember only the pointlessness of the lesson that day. The guilt won out, I lost faith in America the day I found the limits of my bravery and my honesty.

Today, on another Monday with similarly still air, I find myself sighing yet again the same sigh, the eternal sigh of those subject to the violence of a country whose benevolence they sought pleading. I understand now it’s the same sigh I heard as I read Douglass or in Sheppy’s anger explaining Dred Scott. The eternal sigh of America is what I let out this morning, seeing that there will be yet another generation of children for whom Wong Kim Ark will not be a lesson in history or a milestone in the Herculean effort to uphold civil rights, but a promise like the one of the witches in Macbeth. Within this, my last sigh of the day, is the hope Sheppy is still out there, arguing even when it seems ridiculous that jurisprudence is a concept which in the mind of a scared teenager will one day inspire brave, collective action.

God help Sheppy find an answer for those teenagers that isn’t just a sigh, the eternal sigh. And me, because, I lied.

I can’t stop sighing.